Our skin is teeming with microbes. We should learn to love them

_K3OrLz6O42_ai6lkxhl8dr31lql5qjkdozlg3pmnpeqfsalrmgtq5rsxtnapgotphshla3i_LP3sFuFiz7_4iovtirp4zpi2hqdmm6p9o9ashov3ushmbzmgl1xv4fgcgtumpds1wlgnp2z.png)

Billions of bacteria, fungi and viruses live on the surface of our bodies. We are only just beginning to understand the vital role they play in our health and wellbeing.

Your skin is crawling. Zoom in on any square centimetre of the skin on your body and you'll find between 10,000 to one million bacteria living there. Your body is covered in a bustling microbial ecosystem. Pretty disgusting, right?

Or is it? There is growing evidence that our skin microbiota actually plays a crucial role in keeping us healthy and brings a surprising range of other benefits. So don't reach for that antibacterial soap just yet.

You might already have heard of the gut microbiome – the ecosystem of microbes that inhabit your intestines. It is well established that the diversity of this collection of bacteria, fungi, viruses and other single-celled organisms plays an important role in a range of diseases, from diabetes to asthma and even depression. (Learn how exercise can give your gut microbes a boost.)

But it turns out the microbial hitchhikers on our skin can be just as good for us, offering the first line of defence against any pathogens that might be unlucky enough to settle on the surface of our bodies. They also help to break down some of the chemicals that we encounter in daily life and play an important role in the development of our immune systems.

The skin microbiome is second only to our guts when it comes bacterial diversity. This is quite surprising if you think about it. Compared to the safe, warm and moist habitats of our mouths or guts, the skin is a pretty inhospitable place.

"Skin is a very hostile environment compared to other areas of the body," says Holly Wilkinson, a lecturer in wound healing at the University of Hull, in the UK. "It's dry, barren, and very exposed to the elements. Bacteria that live there have evolved over millions of years to cope with these pressures."

And this co-evolution has brought us many benefits.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Certain bacteria stimulate our skin cells to produce sebum, an oily substance that prevents water loss – something that cosmetic treatments try to replicate (Credit: Getty Images)

Not all parts of the skin are colonised equally either. Bacteria can actually be surprisingly picky about where they want to live. Take a swab and run it along your forehead, nose, or back, and you'll find that these areas are brimming with Cutibacterium, a genus of bacteria that has evolved to feed off the oily sebum made by our skin cells to help moisturise and protect the outer layer of our body.

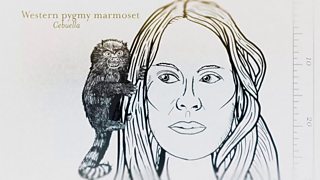

Take a sample from your warm and moist armpit, however, and you'll probably find plenty of Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium. Look between your toes and you'll find an abundance of Propionibactrium species – some of which are also used in cheesemaking along with a wide range of fungi. Dry regions of the skin, such as the arms and legs, are particularly inhospitable to bacteria, and so species that make their home here don't tend to stay for too long. They also tend to play host to a larger proportion of viruses than other external areas of the body. (Of course, our skin plays host to other creatures too, such as tiny mites – see the video below to find out more about them, if you can stomach it.)

Over millennia, these microbes have formed a kind of symbiotic relationship with us humans. The bacteria, fungi and mites living on our skin benefit from a constant supply of rich nutrients. But we rely on our skin microbiome too, as beneficial species help us repel more harmful, pathogenic bacteria by competing against them.

"Just by virtue of the fact that there are all these bacteria already there, it's quite hard for a pathogen to get a foothold," says Wilkinson. "Any bacteria coming in has got to be able to overwhelm the system, but to do so they've got to compete with bacteria that [are] highly evolved to be in this environment."

Skin bacteria can also wage war on potential invaders by producing chemicals that inhibit their growth, or even kill them outright. For example Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus hominis – two commensal species that rely upon us and other animals to host them – produce antimicrobial molecules that inhibit Staphylococcus aureus, a harmful species of bacteria associated with MRSA infections and a common source of skin infections.

Some scientists also believe that, like our gut microbiome, the skin microbiome plays a role in helping to "train" our immune system during childhood, teaching it which targets to attack, and which to ignore. There is thought to be a link between the diversity of certain bacteria on the skin and a lower risk of allergies, for example.

The skin microbiome has other important functions too. For example, it's thought that certain bacteria can help us retain a youthful visage by helping us retain moisture, keeping our skin supple, smooth and plump.

To stop toxins and harmful pathogens from coming in and water from rushing out, our skin contains several layers, with the top being the most impenetrable. The top layer is called the stratum corneum and is formed from dead cells called corneocytes, interspersed with fatty molecules known as lipids.

"It's very tough and waterproof, hence why we don't dissolve when we go out in the rain," says Catherine O'Neill, professor of translational dermatology at the University of Manchester.

Beneath the stratum corneum you have layer upon layer of live skin cells called keratinocytes. There are tiny gaps between these skin cells through which water could leak. To stop this from happening keratinocytes produce lipids, which help repel moisture.

"It's kind of like a brick-and-mortar kind of structure," says Wilkinson. "You've got the cells, and then in between the cells you've got all of these lipids that act as part of the barrier as well. They act like a glue keeping everything together."

So, where do bacteria come into this? Well, it turns out that some of the more helpful bacteria that live on our skin not only produce lipids themselves, but send out signals telling our skin cells to produce more lipids too. For example, studies show that Cutibacterium stimulates the skin to produce more of the lipid-rich sebum, which reduces water loss and increases hydration. Staphylococcus epidermidis also increases levels of skin ceramides – lipids that act like a glue holding our skin cells together to keep our skin barrier intact and healthy.

So far so good. But what happens when the delicate balance of the skin microbiome is disrupted? Skin "dysbiosis" has been linked to conditions from atopic dermatitis (a type of eczema), to rosacea, acne and psoriasis. Even the presence of dandruff on the scalp is associated with a particular type of fungi. Malassezia furfur and Malassezia globosa fungi produce a chemical called oleic acid, which disturbs the stratum corneum cells on the scalp, provoking an itchy inflammatory response.

However, in each of these cases it is difficult to establish whether the disease state is caused by the skin microbiome, or whether the skin microbiome itself has changed as a consequence of the disease.

There's even some evidence to suggest that the skin microbiome could protect us from the some of the harmful effects of UV radiation

One phenomenon that we can, at least partially, blame on bad bacteria is skin ageing. As you get older, the types of bacteria that live on your skin change. You tend to find less of the "good" species that protect against infections and help keep skin moist and hydrated. Instead you get higher levels of the harmful pathogenic bacteria. This has implications for skin healing.

"Older people tend to have drier skin that's associated with lower amounts of the types of bacteria that help with lipid production," says Wilkinson. "That leads to increased risk of skin infections, as, it reduces skin integrity. In older people, you're more likely to get a spontaneous wound appearing because you lose that integrity of the skin."

Unfortunately, "bad" skin bacteria may also interfere with wound healing. Research by Elizabeth Grice, a professor of dermatology and microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania, has shown that wounded mice lacking a skin microbiome take much longer to heal.

Meanwhile work at the Hull York Medical School by Wilkinson's colleagues has shown that a person's skin bacteria can predict whether they will heal from a chronic wound or not. Chronic, non-healing wounds are a life-threatening skin condition affecting one in four diabetics and one in 20 people over the age of 65.

"Hopefully at some point in the very near future we might be able to use that kind of strategy to figure out which patients are going to be most at risk of developing a non-healing wound, and provide that early intervention before it gets to the stage where they need to have a leg amputation, or develop a really nasty infection," says Wilkinson.

Indeed, certain strains of Staphylococcus aureus are associated with delayed healing. However, the exact mechanisms by which this pathogenic bacteria interferes with healing are uncertain.

"Staphylococcus aureus produce enzymes that can help them invade and digest the tissue around them," says Wilkinson. "But they can also interfere with your immune function, causing your own system to turn against you.

"The main driver of poor healing in chronic wounds is the fact that the wounds are stuck in that inflammatory phase, and they can't get out of it. So having the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria there just keeps it in this perpetual loop of inflammation."

Getty Images

Getty Images

The balance of bacteria species on your skin can play a role in how your skin ages (Credit: Getty Images)

Other studies have found that some skin microbes may actually be beneficial for wound healing.

There's even some evidence to suggest that the skin microbiome could protect us from the some of the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation. When UV radiation hits the skin it can damage DNA. However, skin cells have an inbuilt protection mechanism.

"Essentially they stop reproducing and then the skin goes through a series of checks to repair that damaged DNA," says O'Neill. "If it can't repair it, the cells will basically kill themselves."

However, in a recent unpublished study, O'Neill found that if you remove the microbiome, then skin cells carry on dividing even when they have damaged DNA.

"Obviously, this is a really important protective mechanism against tumours," says O'Neill. "And clearly the microbiome seems to be a big part of that."

Research in mice has also indicated that the microbiome may also help to modulate the way our immune system responds to UV exposure, helping to prime it to fight off potential infection. UV light is known to suppress our immune response while it can also damage the skin, offering pathogenic bacteria the opportunity to invade our bodies. It appears the skin microbes help to induce an inflammatory response to UV light exposure, priming our bodies to fight off infection.

There's even some evidence to suggest that the skin microbiome could influence the gut. For example a recent study shows that skin injuries can lead to significant changes in the intestinal microbiome, increasing a person's susceptibility to gut inflammation. Studies also show that Malassezia restricta, a fungal member of the skin microbiota, is associated with Crohn's disease and can exacerbate colitis.

"Everyone knows there is gut-skin axis, whereby eating a poor diet can give you bad skin, but the idea that when something is wrong with our skin microbiome, that it could maybe give us diarrhoea. That's completely crazy," says Bernhard Paetzold, cofounder and chief scientific officer of S-Biomedic, a company which aims to treat conditions like acne by restoring the skin microbiome. "However, very recently, we have started to understand that this crosstalk is bidirectional and in fact there is a skin-gut axis."

There's even a theory that your skin microbiome could affect your brain, although the jury is still out on this. For example, a recent study took 20 healthy volunteers and asked them to perform a range of cognitive tests while measuring their brain activity. It found that removing bacteria from the skin on the forehead increased the attention level of participants.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The cosmetic products we use and the environment around us all play a role in altering the microbiome of our skin (Credit: Getty Images)

As we learn more about the skin microbiome and its role in health and our wellbeing, there is growing excitement among scientists about the role it may play in other aspects of our lives.

Treatments

So, could we improve our health by swapping our bad skin bacteria for the good guys – a kind of microbial skin transplant, if you will. Possibly, although to do this you'd have to wipe out the existing microbial community on your body, which could cause other problems, including the risk of driving antibiotic resistance.

Our skin microbes are also heavily influenced by our environment, so we would also need to consider how the world around us contributes to the diversity of different bacteria, fungi and viruses on our bodies. Even the cosmetics we use can alter the make up of our skin microbiota in ways that are only just starting to be understood.

Some companies believe it may be possible to stimulate the growth of "healthy" microbes by treating the skin with "prebiotics" and "probiotics" to feed the good bacteria, or apply bacterial proteins or lipids to your face directly. There is little published evidence for how effective this is, but there are some signs it can tweak the balance of different skin bacteria.

Wilkinson is even researching whether special viruses that infect bacteria – known as bacteriophages – and the molecules they produce, could be used to wipe out Staphylococcus aureus in a targeted way without harming the rest of the microbiome.

"The idea is that by depleting the pathogenic bacteria, and allowing the natural microbiota to be restored, you can accelerate wound repair," she says. "So that is all very exciting for us, and hopefully that will eventually lead to a step change in the way that we approach treating these infections."

Election Roadshow

41 killed, 12 rescued after boat capsizes in NW Nigeria: official

_Tce5QlMl8J_e9eft0xea8kg8tiiszpkjr0p1pmdtsvjz97goz2mntatyqkphfyf3otizmo7_AaMVPpql80_ydvwi8zkimpcwdzsmzfbm1sx7efuwlmwplnwvpeuzqevrxiiuraklsc5c5vw.jpg)

Iran sends Chamran-1 research satellite into orbit

Jordan PM resigns after general election

Modi 3.0 prioritizes science, technology, and security with landmark ini…

Election Commission consults PM Oli on by-election at local level

'We want identity and respect as human,' cry out sexual and gender minor…

Comment